United States | Maryland, New York | Jun. 14, 1934

W. E. Cadwell, a trooper from Schenevus, headed west with his wife toward the Woodbine Inn the night of Jun. 14 1934. He had received a call at about 10:30 p.m. from the inn’s owner, Eva Coo. The woman held concern over the absence of her handyman, Harry Wright, whom she claimed left the inn alone on foot at 7 p.m. to inquire about a painting position at another property. Wright was supposed to return with Coo’s lover, Harry Nabinger, but the pair never showed. Coo asked whether any accidents had been reported that night.

Passing the inn, Cadwell honked his horn to alert Coo of his presence before proceeding down the road to search for Wright. It wasn’t long before he saw the body, lying on it’s back in a roadside ditch only a few hundred feet from the inn. Cadwell drove ahead to prevent his wife from seeing before pulling over. Stepping out of the car, he walked down to the body and confirmed the man to be Wright. Poor bastard must have been struck by a truck.

Eva Curry was born in Haliburton, Ontario 1888. At the age of 17, she moved to Toronto to study nursing where she met a railroad worker named William Coo. The two engaged in a slight courtship before marrying around 1904. They separated after 14 years, although some reports claim it was earlier. Just after Eva left, William’s house burned in a fire.

Eva kept the last name and moved to Upstate New York in the 1920s where she set up a hidden bar at a farmhouse in North Harpersfield. In the age of prohibition, bootlegging liquor to men was enough to make a prosperous living, but few customers were found in the countryside.

Looking to earn greater profit, Coo purchased property in Oneonta, a booming railroad town in Otsego County, where she set up a brothel and continued to sell booze among the masses. Her operations are said to have began close to the teacher’s college on Brewer Ave., but were relocated to the second floor of an apartment building on Chestnut St.

To keep her business running, Coo needed connections that would shield her from the law. She used charisma to befriend prominent figures within the area, including politicians, police troopers and lawyers, all of whom would frequent her establishment. Coo pulled in enough gain to purchase several luxury items, including furs and many vehicles.

Word eventually spread of Coo’s cathouse to neighborhood wives, resulting in attendance to drop. It was around this time when Coo started to loose police protection. Her apartment was raided by federal agents Oct. 24, 1927, who confiscated Coo’s liquor supply. Furthermore, she was forced to pay a $425 fine after pleading guilty to alcohol possession Jan. 10, 1928.

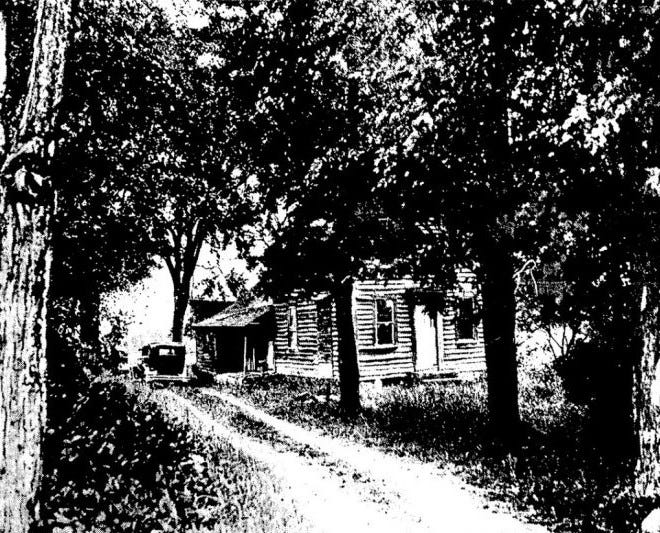

Coo began looking for property outside the city and purchased a roadhouse in the town of Maryland Aug. 14, 1928. Her speakeasy resumed under the name ‘The Woodbine Inn,’ but everyone called it ‘Little Eva’s Place.’

The coroner ruled Wright’s death as an accidental hit and run, but certain details about it seemed off. The body was located nearly 10 feet from the road, farther than would be expected if he was just struck down. In addition, no physical evidence, such a broken glass or skid marks, were found at the scene.

On the day of Wright’s funeral, the coroner received a call from Earl Ames, a Metropolitan Life Insurance agent, asking him to reopen the case. Earlier that morning, Coo approached Ames with three life policies on Wright, her being listed as the beneficiary. Ames noted Coo seemed nervous and that her hands shook as she signed her name.

An autopsy was scheduled before the body was buried and it found that Wright’s ribs had been crushed in, penetrating both his left lung and heart. It was noted to have been caused by a blow of considerable force. The severities of the injuries indicated that a simple hit and run was not the root cause. Foul play became suspected.

Martha Clift was a waitress at the Central Inn in Worcester, NY. She met Coo through her brother and the two hit it off as friends. Coo offered Clift a hostess position at her brothel and she began working there in 1932.

Prohibition ended with the passing of the 21st amendment Dec. 5, 1933. Coo ran her business as normal, but would continue to sell booze without a license. Legal bars began opening within the city limits and her past cliental, who’d rather not be caught in a raid, flocked to those places. By 1934, her inn was near empty.

With the addition of the 1929 stock market crash and the discontinuation of a passenger rail line near Maryland, Coo found herself in financial trouble, having several unpaid taxes and mortgage payments on her properties.

A trespassing claim was filed to police by a man named Ben Fink Jun. 15, 1934. He reported an encounter his wife, Iva, had at their property on Crumhorn Mountain the night before. She claimed to have confronted two women parked at her mother’s old farmhouse, one of whom she identified as Eva Coo. The license plate on their vehicle was noted.

The vehicle, a Willys-Knight sedan, would be traced to a garage in Franklin. Morris Peak, the garage owner, mentioned Coo had approached him with the claim of having a potential buyer for the Willys-Knight. She said she would send her to the garage within the next few days to inspect the car. An employee of Peak rented the vehicle to Coo’s friend for a test drive on the day of Wright’s death. The woman’s name was Martha Clift.

Through further investigation, it would be found that Wright’s inscription on his family gravestone had been altered. His birthdate, 1880, was changed to read 1885 and a new name was carved below his own.

Harry

1885 -

Eva Coo 1892

Harry “Gimpy” Wright was born Oct. 29, 1880. Following his school years, he found work in his father’s footsteps as both a painter and paperhanger. At the age of 51, Wright’s mother, Hattriet, whom he was still dependent on, passed away. She had been friends with Coo for years and, before her death, asked Coo to take care of Harry if she died. Wright moved in with Coo after Hattriet was buried and would work odd jobs around her property. He was a known drunk who often asked to be paid for his work in booze rather than cash.

From his inheritance, Wright received an amount of $1,820, which he divided among two bank accounts in Cooperstown and Milford. It was observed by tellers that Coo would frequent the banks with Wright to withdrawal large amounts. Both accounts were depleted by Oct. 13, 1931.

Wright had also inherited his parents’ old house, but, like William Coo’s home, it burned down Jun. 14, 1933. The loss was reported by Coo the next day and both she and Wright picked up a check for $350. Another $100 was earned after Coo sold the property lot.

Over the years, Coo would place several insurance claims on Wright’s life with her listed as the sole beneficiary. She began with a $448 policy at Prudential Insurance Company Oct. 19, 1931, but, during her research, found that double indemnity would not be paid to people over the age of 50 on certain policies.

For her benefit, she decided to take a couple years off Wright’s life. She had Clift change the dates in the Wright Family Bible to indicate that Harry was born 1885 instead of 1880, which she, along with Wright, brought to Prudential Insurance as proof of an incorrect listed birthdate Jun. 1, 1933. Coverage on the initial policy was increased to $602.

Next, Coo and her lover, Nabinger, approached a sculptor named Arthur Stanley and hired him to correct Wright’s birthdate on his family plot at a cemetery in Portlandville. She also asked Stanley to add her own name to the gravestone in Wright’s request, claiming Wright wanted her to be buried by his side for providing for him. The deed was done Jun. 2, 1933.

With the help of Nabinger, Coo had taken a total of 20 policies out on Wright from different insurance agencies. In addition, she had Wright sign a will listing her as the beneficiary. Wright now had a worth of $12,900 if he died under accidental causes. With his “50th birthday” approaching, however, that amount would be cut in half.

Coo, Nabinger, Clift and a hostess from the inn, Gladys Shumway, took a trip up Crumhorn Mountain May 30, 1934. Coo claimed she wanted to visit the home her neighbor used to live, but instead, while heading up the road, told Nabinger pull into the driveway of the abandoned Scott house, rumored by many to be haunted. The four got out and roamed the property. Shumway recalled Coo finding a heavy oak mallet on a table inside and carrying it out to the porch. Coo turned toward Shumway and said,

“Wouldn’t that be something to hit someone over the head with?”

Police took Coo and Clift into custody without a warrant the day of Wright’s burial Jun. 18, 1934. They were brought to separate stations and faced at least 36 hours of questioning.

During their interrogation the next day, two state troopers, also without a warrant, searched Coo’s residence. Several insurance policies were found, not only on Wright’s life, but Nabinger, Shumway, Clift and Clift’s two young children.

A confession was received by Clift at 4:15 a.m. Jun. 20, 1934.

Wright was painting Coo’s porch at about 5 p.m. when Coo and Clift pulled behind the inn with the Willys-Knight Jun. 14, 1934. Coo told him she wanted to take some shrubs from the old Scott farm and asked for his assistance.

They arrived at the house at about 8:30 p.m. after waiting for a farmer in a nearby field to leave. Coo stepped out of the vehicle, walked up to the house and came back with something hidden under her jacket. Gesturing for Wright, he got out of the car and proceeded toward her. With his back turned, Coo took out a mallet and swung it against Wright’s head. He fell to the ground and Clift set the car in motion, crushing him beneath the wheels. Clift backed up over the body and turned the car around. Wright, still alive, spoke his last words.

“My God, I see why you got me here now.”

Coo noticed a pair of headlights pulling up the road and told Clift to back the car up over the body. A vehicle pulled into the driveway and out came the property owner, Iva Fink, as well as her friends Ben and Sarah Hunt. The group had been meaning to look at a farm for rent on the mountain that night when they were informed by a nearby resident, Harry Zindle, whom Fink asked to look after the property, that a car had been parked on the land days earlier. Zindle suggested they go up to check if anything was stolen.

Fink accused the women of trying to rob the place, but Coo denied and claimed she was just there to relieve herself. The property was searched, but the house doors were locked and nothing was found missing. Fink looked in the backseat of the Willy’s Knight, but saw only a quilt, two bags and a man’s hat. Coo told Fink to call the police if she didn’t believe her. The Hunts gave room for the women to drive out, but they didn’t move. Clift walked up to the group and said that Coo would be stubborn since they accused her of theft. She assured them that if they left she would get Coo to leave. Fink and the Hunts departed minutes later.

After the group left, Wright’s body was gathered in the quilt and placed on the floor in the back of the Willys-Knight. Clift drove them off the mountain and the pair dumped the body 939 feet west of the Woodside Inn. The quilt was tossed over a fence by Clift in Oneonta and the Willys-Knight was returned a little before 10 p.m. Clift admitted to Gladys Shumway, her roommate, that Coo murdered Wright and Shumway promised to act as Clift’s alibi.

Coo asked her neighbors, Fred Palmer and Clara Meyers, to claim she had been home all night if anyone asked. Not knowing about the murder, they agreed.

Throughout the remainder of the night, Coo acted worried with her patrons over Wright’s absence. She kept checking the road from the window and asked a few friends to search for Wright before phoning Trooper Cadwell.

In her original statement, Clift claimed Coo was the one to have ran Wright over. Coo, who confessed 8:30 a.m. the same day, denied this and stated Clift was the driver. She claimed she was unaware of Clift’s intentions to murder Wright that night.

The women were loaded into separate cars at 7:00 p.m. and taken back to the Scott house Jun. 21, 1934. Hidden within the woodshed was Wright’s body, which had been exhumed earlier that morning. Coo and Clift were forced to reenact the crime and maneuver the body in different locations to match what occurred.

Clift changed her statement Jun. 23 and admitted to being the one who drove the vehicle after being offered the chance to plead guilty to murder in the second degree with a recommendation of 20 years to life. She claimed to have been offered $200 for her part in the crime, which she was planning to use to purchase the Willy’s Knight. In her refined confession, Clift added that Coo hit Wright over the head with a mallet before she ran him down.

Harry Zindle, the man who alerted Fink of their presence, testified that he went to the Scott house May 30 after Coo’s initial visit with Nabinger, Clift and Shumway. He claimed to have found a mallet on the porch and placed it on the washstand in the kitchen before locking the doors. A second mallet was seized from the property weeks after the murder by Troopers Cadwell and Kenneth Knapp, but it was never confirmed as evidence.

Wright’s body was exhumed once more to check for head injury Aug. 11, 1934, but it was in too much of a state of decay for determination. Despite Clift’s statement, it is unknown whether a mallet was used.

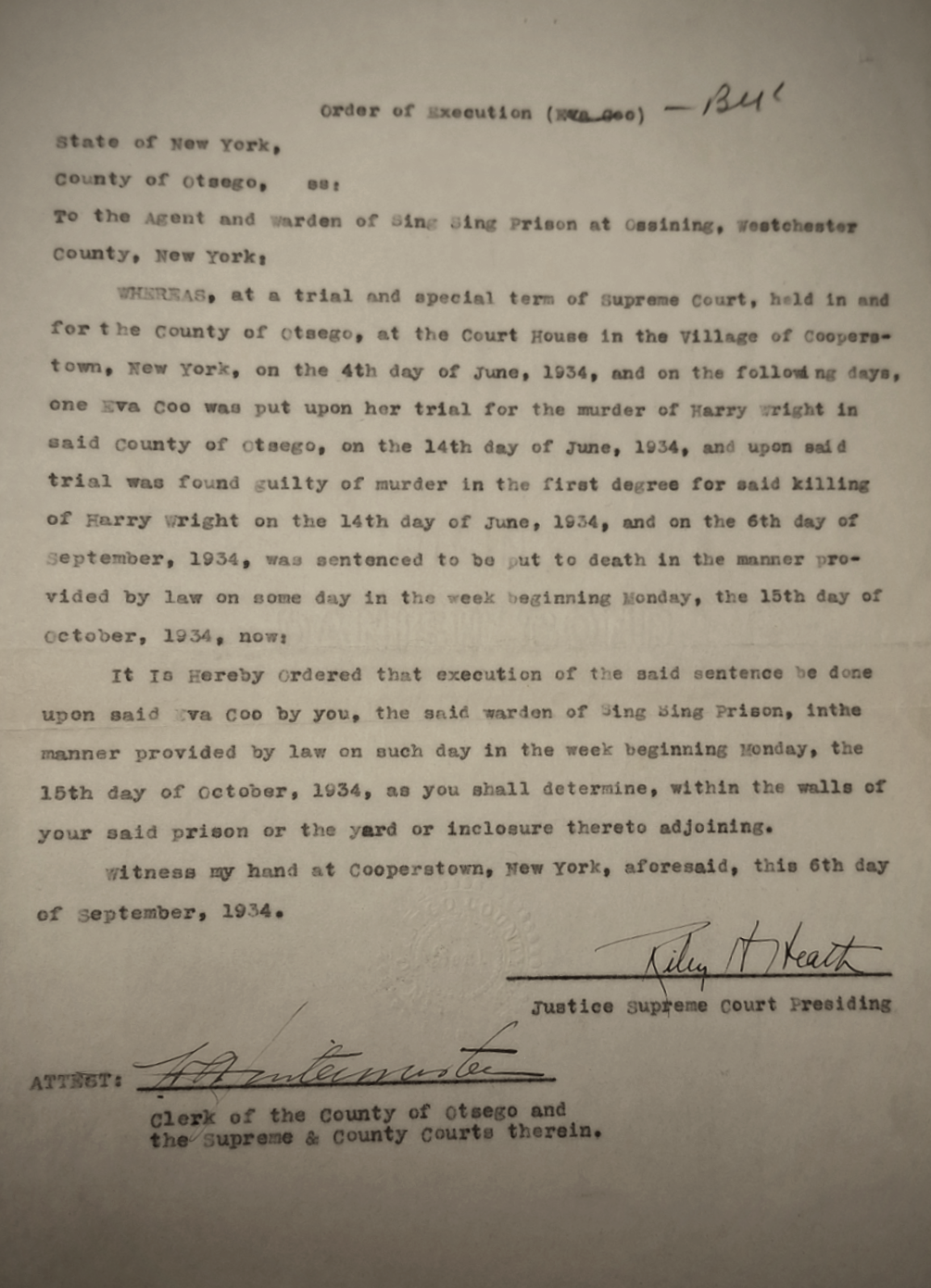

The first day of the Supreme Court was held Aug. 13, 1934 with a verdict delivered Sep. 6, 1934 after only two hours of deliberation.

Martha Clift was found guilty with murder in the second degree and was given a 20 years to life sentence at Bedford Hills Prison for Women in Bedford, New York.

Eva Coo was found guilty with murder in the first degree and was sentenced to death by Old Sparky at Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York.

The Woodbine Inn has long been demolished. Patrons at Nancy’s Bar in Schenevus directed me to it’s former location outside Cooperstown Junction. The building would have been on the north side of Route 7 just a little ways east from the Word of Faith church. Residing in it’s place now is a private two-story home. Of the original structure, nothing remains except a portion of the driveway.

Further east of the land is Peterson Rd., the same path Coo, Clift and Wright took up Crumhorn Mountain. Milford’s town line intersects the route halfway, resulting in a transition onto Buriello Rd. With no leads, I approached a house after seeing smoke from the chimney and asked for directions to where the Scott farm had stood. The man told me to head a couple driveways down, but said the current owners were absent half the year and wanted nothing to do with it’s past history. In finding the location, I did no more than take a glance. As with the inn, the original house no longer stands and was replaced with another building.

The Pine Grove Cemetery in Portlandville extends to the top of a hill overlooking the Susquehanna River. If you follow the main path, Wright’s family grave can be found in the back next to the woods on the far right. Coo’s name was removed, no longer etched in stone. Harry’s birthdate has long been corrected.

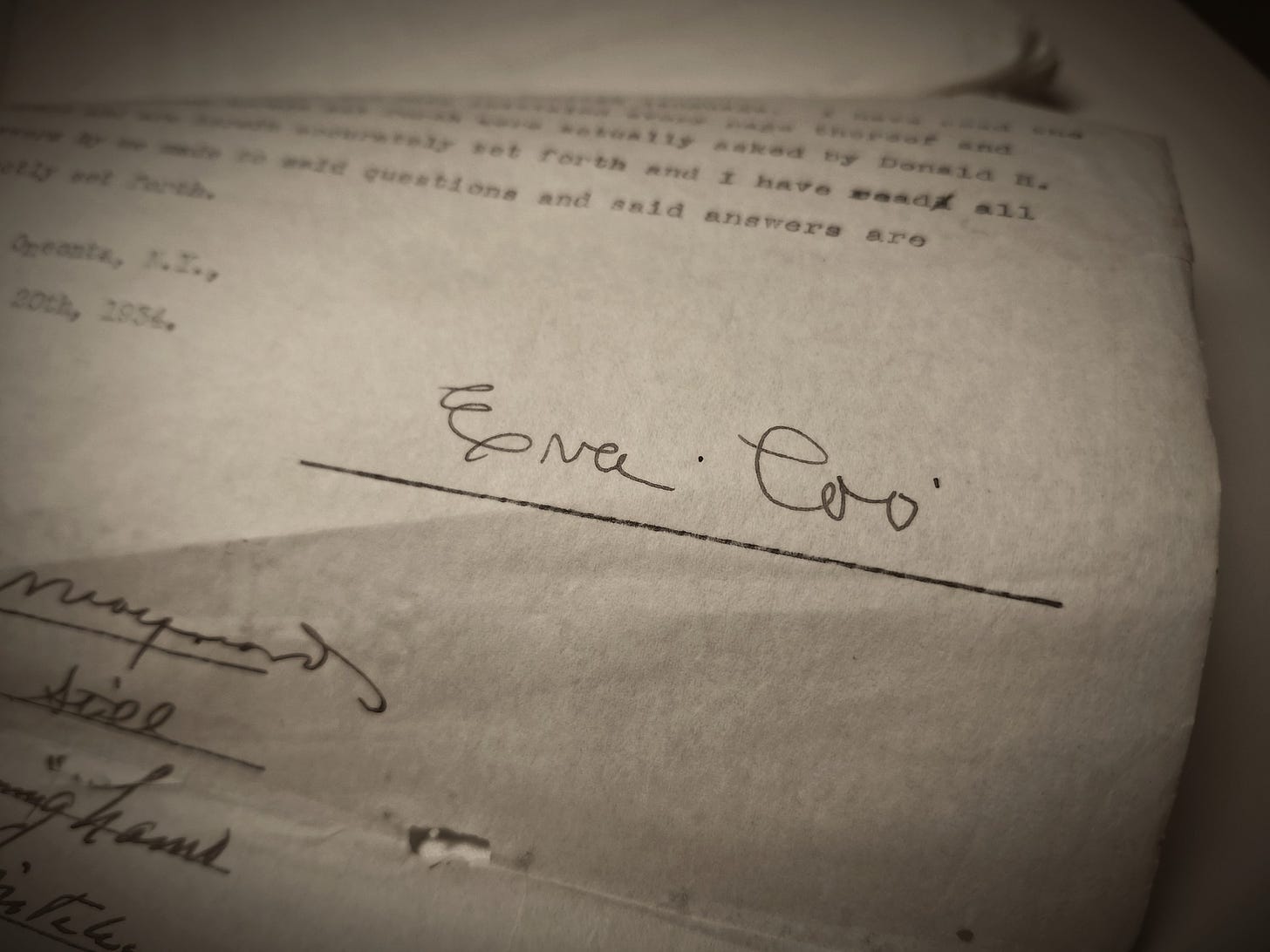

The Otsego County Courthouse is the location where Coo and Clift faced judgement. Upon request, a transcription of the trial can be viewed at the offices in the court’s basement. Several files from the original case are packed in a wooden box as public records, including an indictment for first degree murder, the order of execution and Coo’s signed confession from Jun. 20. The trial transcript is close to 2000 pages long with the box containing both the original typed documents and two print copies divided in four volumes.

Clift was released on parole after 13 years Nov. 11, 1947, taking back her maiden name Compton. She died of cancer at St. Josephs Hospital in Syracuse Jun. 24, 1983 and is buried at a cemetery in Richland, New York.

Thirty four witnesses watched from the side as Eva Coo approached the chair Jun. 27, 1935. She sat down and stared out to the crowd as five guards began adjusting the leather straps.

“Goodbye Darlings.”

~ Carl Nightshade

References

Eggleston, N. (1997). “Eva Coo Murderess,” North Country Books, Inc.

Eva Coo’s Confession (1934, Jun. 20). Otsego County Courthouse.

“Eva Coo Defiant In Chair; Protests Innocence To The End,” (1934, Jun. 28). Oneonta Daily Star.

“Eva Coo Goes To Chair For Insurance Murder,” (1935, Jun. 28). Wisconsin State Journal.

“Eva Coo Implicated In Murder,” (1934, Jun. 20). Oneonta Daily Star.

“Eva Coo,” Murderpedia.

Forrest, F. (1960, Jun. 27). “Murderess Eva Coo Died 25 Years Ago Today,” The Oneonta Star.

“Inquiry Into Maryland Mystery Death Case,” (1934, Jun. 20). The Freeman’s Journal.

Kilgallen, D. (1967). “Murder One,” Random House, Inc.

Learned, A. M. (1934, Jun. 29). “Eva Coo Buried In Lonely Grave Far From Home,” Oneonta Daily Star.

Madampickay, “2 Maryland NY Otsego Cty Bird's Eye View Early 1900s RPPC Real Photo Postcards,” eBay.

“Man Killed, Two Women Quizzed,” (1934, Jun. 20). Ogdensburg Journal.

“Martha Clift Testifies In Coo Case,” (1934, Aug. 24). Plattsburgh Daily News.

“More Secrecy Surrounds Murder Of Harry Wright,” (1934, Jun. 22). Oneonta Daily Star.

“Mrs. Clift Admits Part In Murder Of Harry Wright,” (1934, Jun. 23). Oneonta Daily Star.

“Mrs. Coo Again Accused Of Visit Atop Of Mountain,” (1934, Aug. 23). The Glens Falls Times.

“Mrs. Coo To Die In Chair,” (1934, Sep. 7). Ogdensburg Journal.

“Mrs. Eva Coo Found Guilty, Sentenced To Die Oct. 15,” (1934, Sep. 7). Plattsburgh Daily Press.

“Order of Execution (Eva Coo),” (1934, Sep. 6). Otsego County Courthouse.

Parmeter, B. (2022, Jun. 3). “In my recent Gas Stations presentation I mentioned that it was a work in progress…,” Town of Maryland, New York, Historical Society, Facebook.

“People V. Eva Coo,” (1934). Court Of Appeals, NY. Vol. 1-4, Otsego County Courthouse.

“Promised $200 As Her Share,” (1934, Jun. 23). Ogdensburg Journal.

“Special Grand Jury To Act Monday On First Degree Murder Charges Against Mrs. Eva Coo,” (1934, Jun. 21). Oneonta Daily Star.

Spink, C. (2018, Oct. 8). “Martha J. Compton (1909-1983), Memorial ID: 193846214,” Find A Grave.

Taylor, J. (2023, Oct. 25). “Evil In Otsego County: The Mallet Murderer Part One,” WZOZ 103.1.

“The 1934 Murder at the Haunted House on Crumhorn Mountain,” Memory Ln.

“Woman To Go On Trial For Murder,” (1934, Aug. 13). Plattsburgh Daily Press.

“Woman To Die This Week For $10,000 Murder,” (1935, Jun. 23). The Pittsburgh Press.